How to Create a Well-Tested Design Hypothesis for Better UX and Digital Experience

Let’s start with a confession.

Most design hypotheses are written when the design is already done.

Not mentally done. Actually done.

The Figma file exists. The UI components are named. The prototype link is in Slack. The developer has already asked for specs. And then, somewhere between a calendar invite and a deck deadline, someone says:

“Hey, do we have a hypothesis for this?”

And just like that, a design hypothesis is born. Not from curiosity or research, but from panic.

If that sounds familiar, congratulations. You are working in a normal product team.

This article isn’t here to be afraid of reality. It’s here to explain how design hypotheses can work when they’re treated as thinking tools instead of decorative text.

Design Hypothesis Definition

A design hypothesis is a testable assumption about user behavior that links a specific user problem to a proposed design change and a measurable outcome.

In UX design, a design hypothesis helps teams move from assumptions to validated user-centered decisions. It includes why a design decision is being made, what behavior it aims to change, and how success will be measured.

Unlike opinions or gut-driven ideas, a strong hypothesis is grounded in research.

Why Hypotheses Matter in Modern UX and Product Design

Design hypotheses didn’t appear because designers love structure. They appeared because teams needed a way to explain why a design change existed beyond “it felt right.”

Fast forward to today, and ironically, teams ship faster than ever, but understand user behavior less than they think.

Analytics dashboards are full. Heatmaps glow red in random places. A/B tests run constantly. Yet many teams still can’t answer simple questions like:

-

Why do users hesitate here?

-

Why do they ignore this feature?

-

Why does this work in demos but fail in real life?

A design hypothesis exists to force that conversation early, before opinions harden and solutions become personal.

The work is not to slow teams down, but to stop them from sprinting confidently in the wrong direction.

Why Hypothesis-Driven Design Improves UX and Digital Products

Using hypothesis in design is not like a fancy phrase for “we like data.” It’s a way to stop guessing and start learning.

Design teams can take help from it:

-

They avoid costly rework by testing assumptions before the code ships.

-

It keeps designers, developers, and stakeholders singing from the same page (or at least humming in harmony).

-

It improves conversion, usability, and engagement without depending on gut feelings.

-

They build products that actually solve user problems, not the ones we think they have.

By defining what success looks like before implementation, they can skip endless, directionless iterations and fewer debates end with passive-aggressive Slack messages. This approach is commonly known as hypothesis-driven design, where learning is prioritized over assumptions.

How UX Research Informs Design Hypotheses

The connection is simple: research tells you what’s actually happening with users, which then informs why you might consider changing something.

1. Quantitative vs Qualitative UX Research Data.

UX research comes in two flavors, and both are equally guilty of being misinterpreted if you don’t pay attention.

-

Quantitative data is the “what” of user behavior: This includes click-through rates, drop-offs, bounce rates, and time-on-task. It’s satisfying because numbers feel precise, like math. But don’t be fooled. Numbers tell you what users do, not why.

-

Qualitative data, on the other hand, is the “why”: This contains usability tests, interviews, open-ended surveys, and even those offhand comments from support teams that make you squint and say, “Wait, really?” It’s messy, subjective, sometimes contradictory, but it’s where insights live.

The magic happens when you combine the two: numbers tell you where to look, and human stories tell you what to do about it.

2. Turning UX Research Insights Into Testable Assumptions.

Here’s where most teams stumble: collecting research is easy; turning it into something actionable is hard.

Good hypotheses come from patterns, not anecdotes. If three users struggle with a form and one user clicks randomly, don’t overreact to the one-off. Look for trends across sessions, analytics, and feedback.

Once you spot a pattern, ask yourself:

-

What friction are we actually trying to solve?

-

What assumptions about user behavior are we making?

-

How could we test those assumptions in a real experiment?

A research insight becomes actionable only when it evolves into a clear, testable claim. For example:

“Users abandon the onboarding flow because it interrupts their primary task, not because it’s too long.”

That’s your seed for a design hypothesis, grounded in evidence, not opinion. It is ready to guide real decisions instead of adding mistakes to a deck.

Core Components of a Strong Design Hypothesis

A strong design hypothesis is a testable story that connects user pain to design action to a measurable result. Getting these components right can save weeks of wasted work.

-

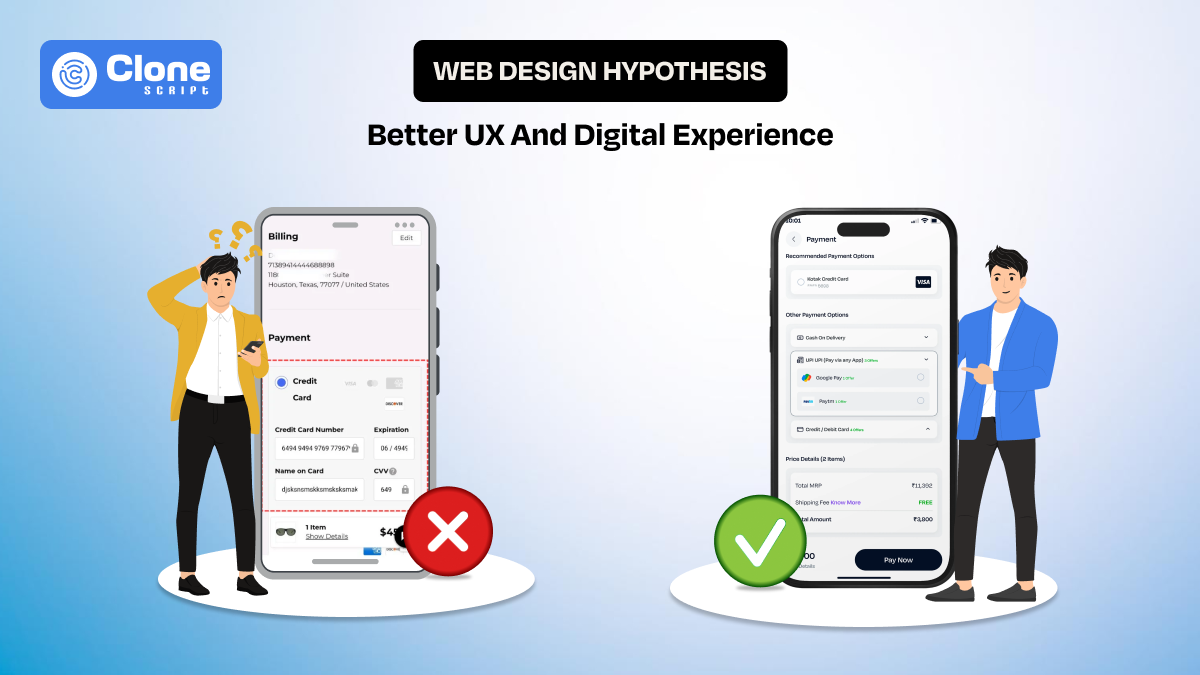

User Problem Statement.

Every good hypothesis starts with a problem, not a solution. This is where you get brutally honest about what’s frustrating your users.

Think in terms of behavior, not opinions. Instead of writing:

“The interface isn’t pretty enough.”

Try something like:

“Users skip the checkout flow midway because they’re unsure if their payment will succeed.”

Notice the difference?

One is subjective; the other is observable, measurable, and actionable. A clear problem statement sets the stage for everything else.

-

Proposed Design Change.

Once the problem is defined, the next ingredient is the design change. This is a specific, tangible action you’re going to test.

For example:

“We will add real-time payment validation and a visible confirmation step to reduce user uncertainty.”

Keep it precise. Vague statements like “make it simpler” or “improve clarity” are tempting but useless. Your proposed change should directly address the behavior you observed in your problem statement.

-

Expected Outcome and Success Metrics.

Finally, a hypothesis without measurable outcomes is just a rough plan. Decide how you’ll know if the change worked. Choose metrics that reflect the behavior you’re trying to influence, not vanity numbers.

For instance, following the previous example:

-

Primary metric: checkout completion rate

-

Secondary metric: time-to-complete the payment step

-

Supporting observation: fewer support tickets related to payment confusion

By defining outcomes upfront, you create clarity, reduce endless debates, and avoid the trap of “we shipped it, therefore it worked.”

A Step-by-Step Framework for Creating a Well-Tested Design Hypothesis

A sequence of thinking steps that prevent you from jumping straight to a solution because it feels right. You need clarity, patience, and just enough discipline to slow down before opening Figma.

Step 1: Define the UX or Digital Experience Problem.

Start by naming the problem in plain language. Not the design flaw. Not the missing feature. The experience problem users are having.

If your problem statement starts with “The UI doesn’t…” you’re probably already in solution mode.

A better starting point sounds like:

-

“Users hesitate before completing this action.”

-

“People abandon this flow after starting it.”

-

“New users don’t seem confident about what to do next.”

This step is about observation, not blame. You’re describing what’s happening, not why it’s happening yet. Getting this wrong means everything that follows will be neatly structured and completely useless.

Step 2: Identify the Target User Segment.

Here’s a mistake designing teams make all the time: they write hypotheses for “users.”

All of them. At once.

In reality, different users struggle for different reasons. A first-time visitor behaves nothing like a pro user. Someone on mobile has very different constraints than someone on a desktop with time to spare.

So be specific. Ask these questions:

-

Who is experiencing this problem most?

-

In what context does it happen?

-

What’s at stake for them in that moment?

The more focused the user segment, the more meaningful the hypothesis, and the easier it is to test without muddy results.

Step 3: Analyze User Behavior and Friction Points.

Now comes the part where you stop guessing and start paying attention.

Look for friction in places like:

-

Repeated clicks or backtracking

-

Hesitation before action

-

Unexpected drop-offs

-

Workarounds users invent on their own

This is where analytics, session recordings, usability tests, and qualitative feedback come together. The goal is to collect more data and identify patterns.

If you hear yourself saying, “That’s weird, users shouldn’t do that,” you’re probably staring directly at the friction you need to understand.

Step 4: Write a Clear and Testable Design Hypothesis.

Only now do you write the hypothesis.

Not earlier. Not while sketching, prototyping, and wireframing. Not because someone asked for it in a deck.

A strong hypothesis connects three things:

-

The observed behavior

-

A suspected cause

-

A change worth testing

For example:

“We believe users abandon this step because they don’t trust what happens next. If we make outcomes clearer earlier in the flow, users will move forward with more confidence.”

It’s specific, slightly uncomfortable, and very capable of being wrong, which is exactly what you want.

Step 5: Align Stakeholders and Technical Constraints

This step doesn’t get enough attention, but it’s where hypotheses succeed or quietly stop.

Before testing anything, check the hypothesis with:

-

Developers who understand system limits.

-

Stakeholders who care about outcomes.

-

Anyone who might later say, “That’s not what I thought we were testing.”

Alignment here is about agreement and shared understanding. When everyone knows what’s being tested and why, results are easier to trust, even when they’re inconvenient.

How to Validate Design Assumptions Before Execution

You think users want a simpler checkout flow, but unless you check, that assumption could be completely wrong.

There are two practical ways to do this before touching Figma UI design or front-end code:

-

Desk Research and Competitive UX Benchmarking.

Before you reinvent the wheel or worse, the square wheel, look around. Desk research is your best friend here. Check out competitors' strengths and what they missed, industry patterns, and case studies.

Ask questions like:

-

How are other products handling similar flows?

-

Which interactions feel familiar to users?

-

What has been proven to increase adoption or reduce friction?

This doesn’t mean copying completely. It means observing patterns, learning what works (and what fails spectacularly), and building hypotheses that are grounded in reality, not just gut feeling.

-

Rapid User Feedback and Early Concept Testing.

Next, get humans involved as early as possible. Even a 5-minute hallway test can reveal whether your assumption is off-base.

-

Sketch a concept and ask users to “think out loud.”

-

Share a low-fidelity prototype and watch for hesitation or confusion.

-

Validate that your proposed change actually addresses the observed problem.

The goal is to validate the design and confirm whether your hypothesis is worth investing in or if it’s already dead on arrival.

UX Testing Methods to Validate or Disprove a Design Hypothesis

Once your hypothesis is written and your assumptions are validated, it’s time to test it in ways that actually answer the question.

The right testing method depends on your hypothesis, the problem, and what you actually want to learn. Here’s how the modern UX toolkit tackles it:

-

A/B Testing and Multivariate Testing in UX.

These methods are great when you want quantitative evidence.

-

A/B testing: Compare a single change against the current version. Did it improve conversions? Reduce drop-offs?

-

Multivariate testing: Compare multiple variations of elements simultaneously to see which combination works best.

The key here is framing the test against your hypothesis. Without a clear expectation, A/B tests are just numbers with no meaning. Remember: the intent is to learn.

-

Usability Testing and Behavioral Analysis.

Numbers tell you what happened; humans tell you why. This is where qualitative methods shine.

-

Watch users interact with your prototype. Note hesitation, confusion, and workarounds.

-

Conduct think-aloud sessions where users narrate their decisions.

-

Analyze behavioral patterns across sessions and spot consistent friction points.

These insights don’t just validate or invalidate your hypothesis; they generate the next one. A failed test can be more valuable than a “successful” one because it points directly to what needs fixing.

Measuring the Impact of a Design Hypothesis on UX and Business Metrics

You’ve written the hypothesis, tested assumptions, and run experiments. Now comes the hardest part: the results without falling into the “it worked because I said so” trap.

-

Selecting the Right UX and Business KPIs.

Metrics are tempting. They glow on dashboards and make you feel productive. But not all metrics are created equal.

Pick KPIs that align with both user behavior and business outcomes. For example:

-

UX metrics: This includes task completion rate, error frequency, time-to-complete, and drop-off points.

-

Business metrics: This includes conversion rate, retention, revenue per user, and support ticket volume.

The trick is to select one primary KPI that directly reflects the hypothesis, plus a few secondary metrics for context. Avoid tracking 37 “nice-to-haves” just to make the data look busy. This is a classic trap that turns insights into noise.

How to Interpret UX Test Results Without Bias?

Humans are wired to see patterns, even where none exist. Web UI designers fall prey to confirmation bias: interpreting neutral or messy results as “good enough” simply because they fit what they hoped would happen.

To avoid this issue, pay attention to the following:

-

Be honest about the data. Did the hypothesis succeed, fail, or reveal something unexpected?

-

Separate signal from noise. One outlier session or metric spike doesn’t define success.

-

Accept failed hypotheses. If your assumption was wrong, that’s not a failure. It’s insight.

The goal is to celebrate “wins” in a vacuum with learn what drives behavior, iterate thoughtfully, and improve the digital experience for users who actually matter. For example, if you've identified the website's hero section as having issues in terms of conveying the message, the CTA placement, or anything else, it has to be resolved through the proper design hypothesis explanation.

Conclusion

Design hypotheses are thinking tools. They help design teams stop guessing, start learning, and focus on real user behavior instead of gut feelings. The best ones are messy, slightly uncomfortable, and capable of being wrong. When grounded in research, tied to measurable outcomes, and tested thoughtfully, they guide design decisions, reduce rework, and align stakeholders. And yes, even if your first hypothesis fails spectacularly, that’s still progress.

In the end, hypothesis-driven design is about learning faster, designing smarter, and keeping users at the center of every digital experience.

BTC - Bitcoin

BTC - Bitcoin

USDTERC20 - USDT ERC20

USDTERC20 - USDT ERC20

ETH - Ethereum

ETH - Ethereum

BNB - Binance

BNB - Binance

BCH - Bitcoin Cash

BCH - Bitcoin Cash

DOGE - Dogecoin

DOGE - Dogecoin

TRX - TRON

TRX - TRON

USDTTRC20 - USD TRC20

USDTTRC20 - USD TRC20

LTC - LiteCoin

LTC - LiteCoin